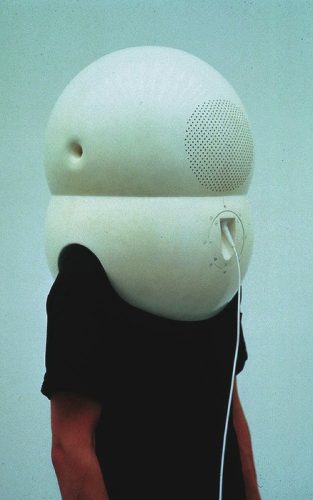

For the past few weeks, I have been wearing an Apple Watch, in an effort to survey the efficacy and implications of wearable technologies. Devices whose “primary functionality requires that they be connected to bodies” (Gouge & Jones, 201), have become the object of study and criticism within the field of rhetorical studies, as they are argued to exist “between media you carry, and media you become”, while integrating a computer “with one’s physical, political, social, and ontological makeup” (Gouge & Jones, 202).

The Apple Watch is marketed as a device that renders the typical wristwatch a relic of the past, through its combining the form of a wristwatch with the technology and functionality of a smart-phone. Additionally, the device employs various modes of self-surveillance, gathering and rendering data relating to bodily heath, function and movement patterns. It is in this sense that wearable technology “becomes you”, as it digitally renders various parts of the wearer’s material/physiological existence through its proximal connection to the body.

The device, referencing in form the unimposing wristwatch, masks this constant informational imposition by posturing itself as a kind of garment, a form of dress or fashion. Noting that, in Judith Butler’s account of identity formation, the subject’s interiority becomes externally fabricated through cultural symbols, Susan Ryan argues in Garments of Paradise: Wearable Discourse in the Digital Age that all forms of dress (not just wearable technology) make rhetorical claims about the wearing subject.

If this is the case, then the Apple Watch can be said to make new, qualitatively distinct arguments about the wearing subject, through it’s monitoring of bodily functions and motion tracking. Perhaps the Apple Watch will produce previously unprecedented arguments about its wearing subject. The watch constructs detailed arguments about the wearer, demands a response, an action on behalf of its argument. In this way, the Apple Watch questions the stability of our own psychological, cognitive means of self-surveillance, and outlines a potential non-human mediation of our daily experiences as self-aware subjects. And seen in this light, wearable technology could offer yet-unheard-of ways of interacting with ourselves and our environments, developing novel motivational structures and habituating new forms of self-analysis.

Some of the experiences I had wearing the Apple Watch fit this emergent-interactive perspective, insofar as the Apple Watch gave me information about myself I had before been unable to access. For example, the watch allows you track your sleep: if you wear it to bed it will build a nightly bar-graph that visualizes your tossing and turning while you sleep, and collocates this with your heart rate and other bodily measures. Since I am always asleep while sleeping, this application gave me access to information about myself that would without the Apple Watch be conventionally inaccessible. The app, and it’s data-driven argument about my sleep cycles, allowed me to consider the conscious practices that lead into and affect my unconscious existence while sleeping. As I could easily reference the nights where I was tossing and turning about, I began to see trends and correlations between my pre-bed rituals and the resultant quality of that night’s sleep.

However, it could also be argued that the Apple Watch is no more than a commercial response to the habituation of constantly accessible, powerful mobile computing, wherein “habit is now a form of dependency, a condition of debt” (Chun, 2-3). This debt, taken as the affordances of advanced mobile computing, could be seen as the motive in the development of continually more streamlined, accessible, and “wearable” devices, which allow a more accommodating, effortless means of quelling our update addictions, and offering new modes of habituation.

I found in my time wearing the Apple Watch an increase in my engagement with my phone. I initially thought the watch would keep me off my phone and engaged with the world, but I instead found myself trapped within a complicated cycle, going back and forth between my watch and my phone. These experiences did not negate the positive experiences I had using the device, but they did call to mind the habituation of device-use, and suggested an irrational addiction to staying constantly updated.

The Apple Watch recapitulates the standard usage of the iPhone within a more streamlined, accessible format, while offering new and advanced ways of collecting data that rhetorically affect the wearer. This affect can be helpful and constructive, though it is not necessarily the case. Calling attention to the kind of arguments that wearable technologies’ make about their users, can help improve the functional relationship between people and their devices, and help us understand the rhetorical situation that these technologies embed us within each and every day.