For my first individual blog post on my research into the six Confederate statues that line UT’s South Mall — as well as my research on similar projects at the University and how they both relate to current national controversies surrounding what the Confederate flag stands for, as well, more generally, race relations in the United States – it seems appropriate to open with an article by Travis Knoll, a history PhD student at Duke University who, as an undergraduate, wrote for The Daily Texan.

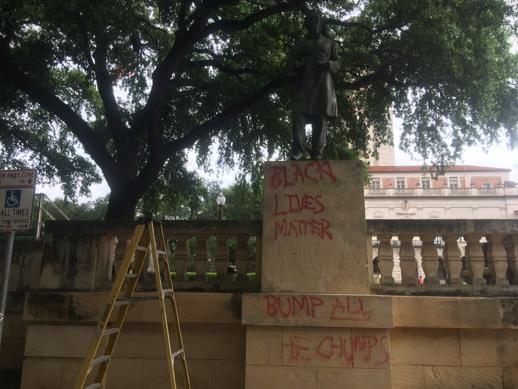

Knoll begins his article “At the University of Texas, Echoes of Its Confederate Past Reverberate in the Present” (accessible here) by surveying recent debate in other newspapers about the statues. Ranging from the conviction that descendants of Confederate soldiers should be able to honor their fallen ancestors to the argument that the presence of the statues makes the South Lawn hostile to African-American students, the positions in these newspapers raise important questions. To what extent does familial obligation override cultural sensitivity? What material presence should history have on campus? And, more broadly, how does a country balance acknowledging its troubled past with suppressing it in favor of political correctness? In fact, these questions all came to a boiling point recently when the words “black lives matter” were spray painted on the statue of Jefferson Davis, the President of the Confederate States of America during the Civil War.

Although Knoll’s article doesn’t explicitly raise these exact questions, he writes, “To answer these questions, readers must look past the Littlefield Fountain, that famous status of WWI triumphalism.” By beginning his inquiry at the Littlefield Fountain, Knolls hits on the significance of the rhetoric of space. That is, what does the placement of the statues in physical space argue? Although there are six other statues that line the South Mall — the Littlefield Fountain, and the Nike-esque figure flanked by a Union solider and a Confederate soldier – is prominently featured in pictures of the University. (For a picture of the Littlefield Fountain, as well as pictures of the some of the other statues lining the South Mall past it, see below.)

As Knoll mentions, the Littlefield Fountain was gifted to the University to commemorate the Allied victory of WWI. Keeping this information in mind with the fact that the six Confederate statues are significantly less prominent, an argument seems to be being made by the placement of the statues collectively for concealment. While this argument may not be intentional, being aware of it is essential to understanding the larger debate surrounding the statues.

The question of the rhetoric of space implicit in Knoll’s article connects to Carole Blair’s chapter in Rhetorical Bodies, “Contemporary U.S. Memorial Sites as Exemplars of Rhetoric’s Materiality.” At the beginning of the chapter, she states, “Materiality [in this case, the physical materiality of the statues] . . . has rarely been taking as the starting point or basis for theorizing rhetoric” (18).

Looking towards the augmented reality app (to see the blog post for the actual project, click here), then, a logical place to start for its educational content would be the Littlefield Fountain and its physical and historical relations to the Confederate statues. It’s my hope that an AR app will make these relations more prominent and less obscured by the geography of space itself.

*For more information on how UT specifically is dealing with the Confederate statues on campus, the University’s commission report can be accessed here.

Featured image: Wikipedia. http://www.wikiwand.com/en/Littlefield_Fountain.

[…] (you can read the inscription in Knoll’s article, and, if you haven’t already, in my whole post on it also featured on the DWRL […]

[…] continuing my exploration into the Confederate statues that line UT’s South Mall. Whereas my first post in this series discussed the prominent placement of the Littlefield Fountain, which has, at its […]