So, you might have heard that Taco Bell’s marketing strategy is “on cleek.” (If you get what’s funny about this, read right on; if not: their marketing genius is appropriating and obviously butchering the expression on fleek, derived from African American English and recently popularized on social media.)

It’s easy – and entirely appropriate – to ridicule a corporate exec’s desperate attempts to sound hip and “with it.” But this little episode reveals aspects of linguistic and cultural appropriation that aren’t as easily laughed away.

Mainstream, and especially: corporate, use of African American English (AAE) expressions is going strong on social media, with little understanding of or respect for the original users of these expressions.

when the whole squad looking fresh pic.twitter.com/tDcORwcIE6

— IHOP (@IHOP) November 18, 2014

This weekend I was in Toronto for NWAV, a conference where a lot of sociolinguists got together to talk language, variation, and society. There were a number of talks on social media, but I want to focus on one specifically today. Renée Blake and Mia Matthias discussed “Black Twitter”: AAE lexical innovation, appropriation, and change in computer-mediated discourse.

Appropriation of Black linguistic practices by the White mainstream is a pervasive phenomenon that is about as old as racism itself. But while it has been critiqued in numerous contexts before, description of the processes involved has been largely anecdotal. Blake and Matthias perform careful, qualitative analysis of social media to add systematicity to the picture.

There is a proposed life cycle to the spread of new slang terms from AAE, following four stages:

- The expression is created and used by authentic users in its original context

- Gaining in popularity, the expression acquires a wider authentic audience (e.g young Black people, hip hop practitioners)

- Ubiquitous and diluted use of the term, which gets picked up by the mainstream outside its original cultural context. Your mom’s oven mitts are all of a sudden “on fleek.”

- The expression is perverted outside its original use by culture killers or capitalizers, often corporate entities with an obvious profit motive.

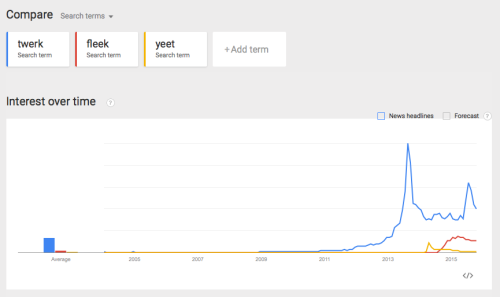

These stages are in loose chronological order, but can and do overlap at any given point. Social media provide an excellent opportunity to study their succession in real time, which is exactly what Blake and Matthias do. They create Google trend graphs for the terms twerk (coined by DJ Jubilee), (on) fleek (Peaches Monroee), and yeet (Lil meatball), which I have recreated here in one diagram:

Looking at these graphs, it becomes possible to identify moments of accelerating popularity, peak usage, and decline for a given AAE term. Blake and Matthias use this information to identify critical points in the trajectory of appropriation and do discourse-centered online ethnography of an expression’s use on Twitter at these times: who is using it, what are they talking about (or talmbout), who are they talking to, etc.? In short: what are the cultural significances of the expression that are not easily captured by raw frequency counts?

With this method, subtle shifts in meaning and usage patterns can be identified that can inform our understanding of how exactly linguistic appropriation proceeds. Early adopters, propagators, and culture capitalizers can be made visible and compared to each other. It would probably be overly optimistic to hope that this is going to change the general pattern of appropriation in the short run, but it does provide the means for a more substantiated and nuanced critique.

You know a stroller is #onfleek when you can go from car to stroll in 15 seconds! @doonausa is… https://t.co/um75dUh6l7

— The Art of Broadcasting (@ArtBroadcasting) October 23, 2015

From an instructor’s standpoint, these techniques could easily be adapted into a classroom project that helps students trace conversations, identify audiences and determine the kairotic moment of key terms in a controversy. Patterns such as the ones above may be particularly drastic for AAE appropriations, and the need for critique most urgent. But any charged term in a given discussion is bound to show developments over time that can be indicative of the larger development of the conversation (think, for example, of the use of a term like terror in post-9/11 American politics).

P.S.: I did not have time in this post to talk about why critique of cultural appropriation is necessary. However, this is a crucial issue that will receive more attention in a post of its own, coming very soon.

Ed. Here it is.