There’s an article that I love, because it analyzes a growing trend regarding people and their relationships with technology. Titled, Communication in online fan communities: The ethics of intimate strangers, author Christine James analyzes relationships between celebrities and paparazzi, celebrities and fans, and fans among themselves. James wants to know why they seem so strange. The answer is simple—tech love is embedded in each, it’s mediating our relationships. Donna Haraway was right, James asserts, about ‘the current state of the human being in modern times, dependent on technology, a blend of human and computer.’ The cyborg is here, everyone…and the cyborg is us.

But the advent of the internet, especially the popularity of constant and immediate Tweets and status updates, and the commodification of paparazzi photos of celebrities, have created an atmosphere in which an illusion of intimacy between celebrity and fan has become not only common, but also seen as a necessary marketing tool key to the celebrity’s success.

Fans tweet to and about celebrities, just like the paparazzi photograph them. Fans believe they’re friends with celebs; celebrities prove they’re a topic of constant online conversation.

The confusion brought on by the illusion of intimacy is important to note. The once simple disorientation between a celebrity and their image is complicated by a love for the websites and Twitter feeds that bring them to us.

I focus on how social movements love to use technology, so I’ve seen this before. But I’ve also noted another mechanism at work. The mechanism, like the illusion of intimacy, has changed what publicity can do for social movements. I call this the phantasy of participation, and I don’t think it should be ignored just because people have started to love Twitter.

When I think about the phantasy of participation, I tend to change the object of study. Instead of the celeb/fan relationship, I care about the reciprocal activist relationship, that is, the relationship between activists recognizable in a community and those who aren’t. And by looking at the reciprocal relationship through the lens of the phantasy of participation, online communities of all sorts—celeb/fan, activist, peer group—take on a different character than the one James offers.

https://twitter.com/deray/status/652517326236033024/photo/1?ref_src=twsrc^tfw

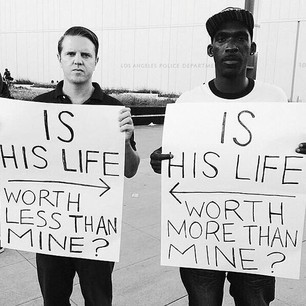

That is, the phantasy of participation isn’t merely a mistaken form of love; it’s a mechanism of social action that can be actualized in meaningful ways. Take Activist Twitter. Before Twitter, the clarion call #BlackLivesMatter was un-operationalized. The honest sentiment was alive and, the need for it devastatingly real; but its means of expression didn’t take on the vibrant quality it now has until the #hashtag became discoverable, searchable, shareable.

The use of the #hashtag function on Twitter helped a social movement organize and then mobilize. In the few years since the beginning of #BlackLivesMatter’s usage on Twitter (after George Zimmerman’s 2013 acquittal of killing Trayvon Martin), that mobilization has created some powerful leaders. Deray McKesson is a good example. McKesson, though aware beforehand, became more actively involved in the movement after the 2014 death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, MO. In part due to the #hashtag, in part as a key member on the ground in the movement, and in part because of Twitter attention from less visible movement members, McKesson now speaks about race relations in the US. He tweets, he speaks publicly (like on CNN or the Nightly Show with Larry Wilmore), and even privately. When Hilary Clinton and Bernie Sanders sat down before the first Democratic Primary Debate in mid October with civil rights leaders, it was with members of the #BlackLivesMatter movement. This time it wasn’t a fan or the paparazzi who tilted their head; it was the Democratic Presidential Candidates. And they weren’t giving attention to a few people, it wasn’t just Shaun King, Johnetta Elzie, McKesson, and others; the Democratic Presidential Candidates were giving attention to a cause.

https://twitter.com/deray/status/644212048201678849/photo/1?ref_src=twsrc^tfw

James uses the word illusion for her depiction of intimacy; I use the word phantasy for my characterization of participation. It’s because participation is always a phantasy of sorts: something is created in that participatory moment that didn’t exist before. Love is involved, too. But when we’re talking about Activist Twitter, it isn’t merely an illusion of love for the tech grafted to the bodies of people, these newly made cyborgs with their Twitters and their Instagrams, their FaceBooks and Pentarists; it’s also a love for the people that become grafted to one another, and a love for the beliefs they share, one of them being a belief in the efficacy of social media.