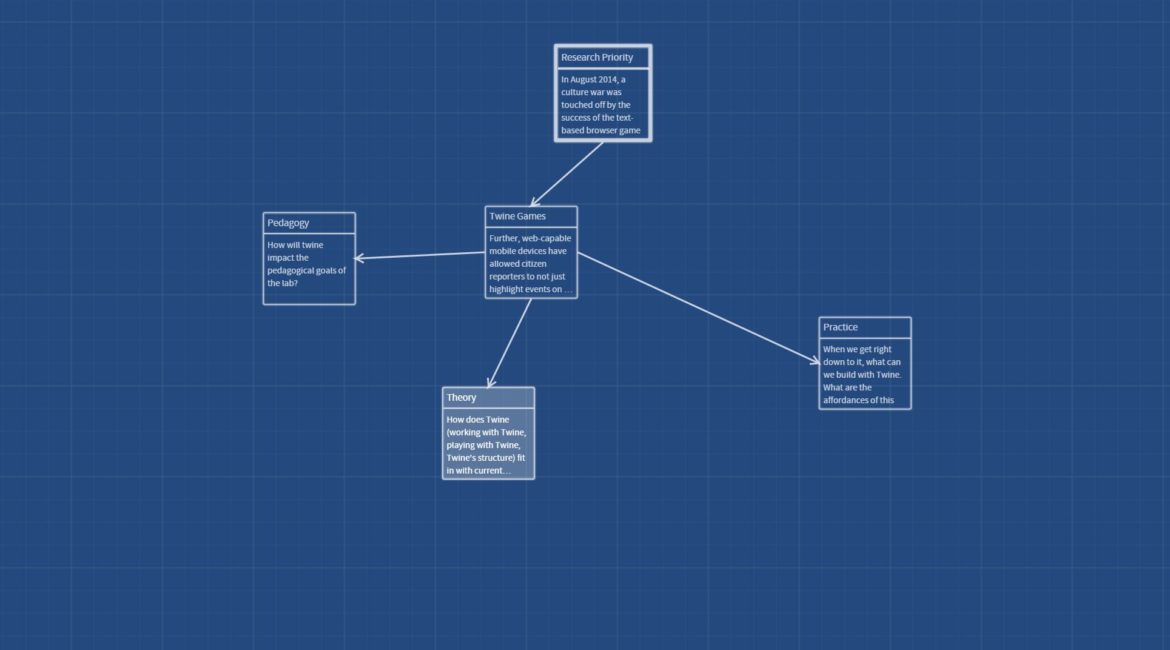

In August 2014, a culture war was touched off by the success of the text-based browser game Depression Quest, which was built with an open-source text-based tool called Twine. Depression Quest, like many Twine games, contests the highly policed definition of a “videogame”; indeed, Twine has empowered a cohort of game designers—many of whom are underrepresented in mainstream gaming culture—to design and disseminate games that critique or altogether abandon the violent, corporate, masculinist, and even humanist values of predominant gamer culture.

All games make arguments, however implicitly; Twine, recently billed by the New York Times as the “video game technology for all,” opens this rhetorical space to voices that have previously been marginalized or altogether silenced. In conceiving of their project, staff members may ask questions, including: Can we teach with Twine? Can we write and produce research with Twine? What kinds of arguments does Twine enable, and how are those arguments foreclosed by traditional technologies of writing? and What makes Twine a fruitful platform for marginalized voices, and how can we recreate those conditions in and with other media?

Suggested reading

Selected Twine games: Queers in Love at the End of the World, by Anna Anthropy (2013); Ultra Business Tycoon III, by Porpentine (2013); Depression Quest, by Zoe Quinn, Patrick Lindsey, and Issac Schankler (2013)

Hudson, Laura. “Twine, the Video-Game Technology for All.” The New York Times Magazine. 23 Nov 2014: MM44.

QED: A Journal of Queer Worldmaking 2.2 (2015): Special issue entitled “Queer Gaming”