You just can’t exaggerate the importance of D&D to all of the many storygames that have followed it. It really did revolutionize the way we look at stories and games and the combination of the two in a way totally out of proportion to the number of people who have ever actually played it. But then, we could make exactly the same statement about Adventure, couldn’t we? Every story-oriented computer game today, including graphical adventures, can trace its roots straight back to Adventure — and from Adventure, straight back to D&D.

I’m not omniscient, but yes, I think we’d have something like Adventure come along, probably sooner rather than later, absent Crowther and Wood. Would it have used such a flexible parser for interaction, though? I don’t know, really. Certainly the many IF conventions that we still employ that have come down to us from Adventure would be a bit different. We can also say for sure that adventure games wouldn’t be called adventure games — that name is lifted straight from the original Adventure, which might perhaps begin to convey to your readers Adventure‘s importance in the scheme of things.

(From an interview with Jimmy Maher in Adventure Classic Gaming)

In the past decade, the digital game space has been democratizing thanks to the increasing affordability of various devices, growing mainstream recognition of its artistic, intellectual, and communal benefits, and consistent calls for accessibility and diversity. At the same time, even as the player landscape and scope of available games expand, the medium itself is undergoing an unexpected contraction, a rhetorical turn towards exclusivity that was not as apparent until a spate of controversies propelled game culture into the public eye. Though Twine (1) had been developed years before, #GamerGate and Zoe Quinn’s Depression Quest (2013) put it on the map as the first contested site in an ongoing “culture war.” My gaming past (and present) has always been more conventional – MMOs and MOBAs and RPGs – but I remember that even as early as 2010, Twine had been an attractive tool for marginalized groups seeking to share personal stories without fear of reprisal or judgment. Twine’s benignity, in fact, is exactly why the reactionary contempt from particular subsets of gamers is notable.

While Twine (1) had been promoted (by word of mouth) as writing software for outlining or creating interactive fiction and Twine (2) is advertised similarly, there are many who currently refer to Twine products as video games – video games with a heavy focus on narrative and far less on graphics, but games with choices and end goals nonetheless. It is this rhetorical evolution that has discomfited some traditional gamers who reject the perceived dilution of the term “video game,” and reject Twine-based products as “games” at all. What are the stakes in ossifying such a definition? How does this impact the gaming industry at all? It could be argued that this is not so much a genre/medium issue as it an indirect method of reconstructing deteriorating barriers to entry. It could also be argued that delimiting “video game” indirectly protects the “gamer” identity in the same manner that the disavowal of mobile games (such as Candy Crush) was clearly meant to exclude women from the “gamer” population. To lessen their potential relevance in marketing and game design.

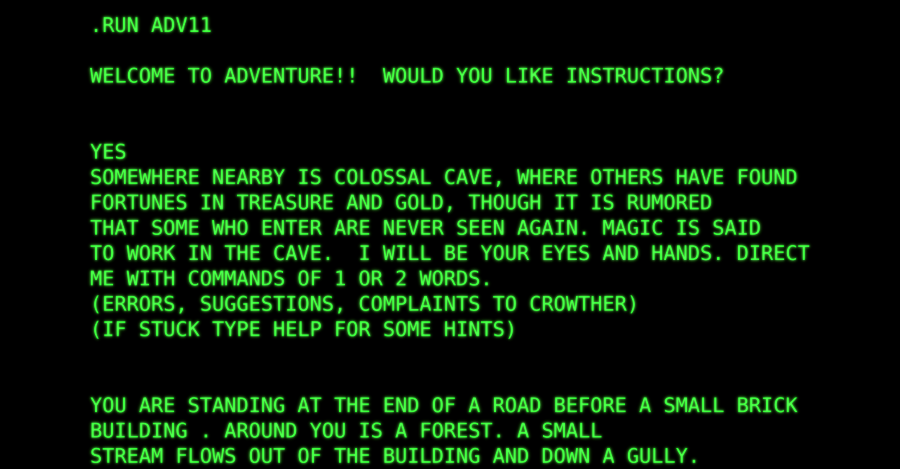

What I find most interesting, though, is that the history of computer games is – must be – conveniently ignored to perpetuate a specific mode of “video game.” In an interview, Jimmy Maher discusses the history of interactive fiction (IF), linking it to “the first-generation home computers that were just beginning to arrive on the market by then.” The graphical capabilities of those computers were so rudimentary that IF, with its emphasis on text, was “one of the most popular forms of computer entertainment during this era” (the 1970s-80s). And Colossal Cave Adventure (Adventure) (1976) was the seminal representative of IF. Though the 1986 version offers accompanying images, the original (featured above) contains only text.

The culture surrounding early video games (IF) should, in fact, appeal to the very gamers who now discount it. It was about open software (“Everyone simply shared their software creations with everyone else”), about innovation rather than exploitation, about free to play, and about accessibility to a range of people beholden to the hardware restrictions of their PCs. People seem to have forgotten that at one point, IF was – without a doubt – considered a video game. What significant difference is there between Pong (1972-3), which continues to be categorized as a video game despite its simplistic mechanics and graphics, and Adventure, which some might now reject by virtue of its IF, Twine-like characteristics?

The resurgence of IF through engines like Twine is a reminder that games and game culture were influenced by ’70s text-based adventures, and continue to be transformed by modern iterations. Disagreements over definitions aside, we must recognize that digital gaming has always involved questions of accessibility, knowledge sharing, and consumer participation, and that it is only a recent revisionist move which has elided IF’s critical role in computer gaming. Without this historical framework, it is too easy to neglect just how much the video game medium requires narrative and a graphical interface and mechanics. To prioritize one without considering the rest is to dismiss the hybrid nature that distinguishes video games from other art forms.

If you’re interested in playing a version of Adventure, click here.

Featured Image: Intro to the original Adventure (1976) game. Image from codersnotes.