There is a fundamental issue with how we (as academics, players, and creators) view game narratives. This particular art form leaves room for player intervention, for changes and transformations, however, such interactivity has done little to push the boundaries of storytelling beyond alternate endings and perpetual quests. Is this as far as stories can go? Linear progressions momentarily disrupted by the novelty of easter eggs and yet-to-be unlocked zones? Mark Danielewski’s The Familiar book series – delivered through a traditional print medium – currently does a more thorough job of reshaping narrative conventions through digital technologies than games themselves do. While the capabilities of digital play have continued to expand, modern games have yet to experiment with the alternate ways stories and story-based experiences can be delivered – and I attribute part of this stagnation to our fixation on “choice.”

[For my purposes here, I focus only on the standard conception of ‘narrative,’ that is, a pre-set story with a beginning and an end; I do not include the spontaneous narrative that is generated by the player as (s)he interacts with the text (the ‘narrative’ of play itself).]

In keeping with my interest in in historicity and Twine, this post discusses a point of intersection between two separate games from two separate decades: Aisle (1999) and The Uncle Who Works for Nintendo (2014). Interactive Fiction (IF) is the narrative component of video games laid bare and delivered through a sparse interface, and so, it is incredibly suited to critiquing and exploring the dimensions of digital storytelling. The narrative choices that are offered in IF are no more restrictive than Pokemon Red‘s (1996) or Assassin’s Creed: Revelations‘s (2011). Aisle and The Uncle Who Works for Nintendo clearly demonstrate that as of yet, game narratives have not innovated any further than the choose-your-own-adventure genre.

The Uncle Who Works for Nintendo is a Twine game created by Michael Lutz, an English PhD student whose website contains a host of other IF experiments. With images and music (credits on his webpage) to go with it, Uncle is an atmospheric and creative use of horror and the Twine engine. What is unusual, is the multiple endings (5) and the ways in which you must alter and time your narrative decisions to “unlock” those endings. The process can be frustrating if the player does not have the patience to alter variables one at a time (I certainly did not) to determine what answer influences what outcome. Lutz provides a final scoreboard to keep track of what you’ve already successfully cleared, and to provide hints as to how to unlock the rest.

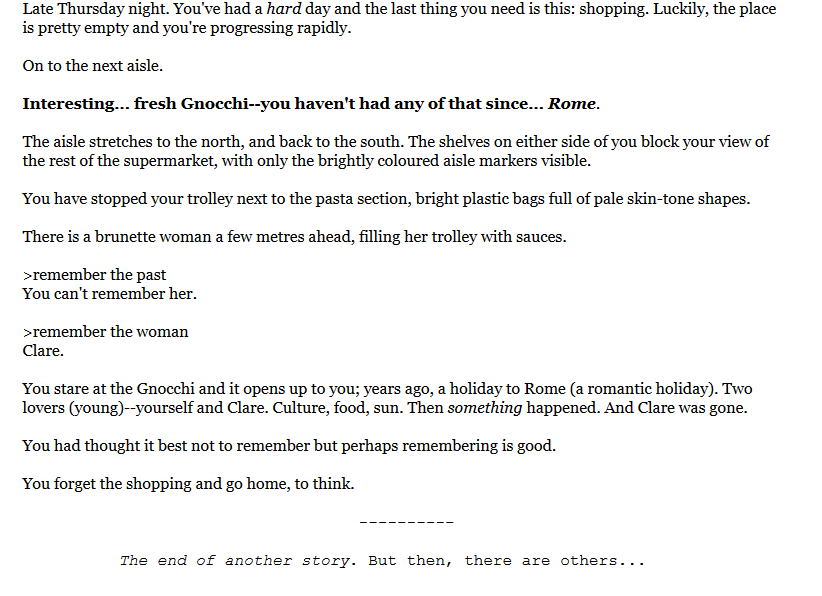

Aisle, by contrast, is an older text-based adventure developed by Sam Barlow through Z-machine. This particular IF is fascinating because it is a “one move” experience. The player inputs one action, and so, their “intervention will begin and end the story.” There are, reportedly, over a hundred different outcomes, but I gathered thirty.

Why have I paired these games together? Because they make use of the very mechanism that many video games depend on to simulate “choice.” However, without distracting or entertaining frills, these two IFs highlight the frustrating and artificial nature of freedom in video game narratives. By the 5th round of Uncle, I had lost interest in the narrative and the play and the atmosphere and everything else that had impressed me; I sought only to obsessively “unlock” the last 2, stubborn endings. With Aisle, I was overwhelmed by the parade of different conclusions, as well as my inability to achieve the actual ending I desired. There was a futility in my 1 choice that I had to remake over and over. Yet, I continued to do so long past reason because I had fixated on the mechanic, on beating it, on solving it.

Whether we play a game that contains a multitude of choices and a multitude of ways in which the environments respond to those same choices, or we play a game that offers a single “intervention” – we risk succumbing to the limiting effects of the “questing” trope, of becoming pure consumers of the quest. In this case, not the “quest” for loot or drops, but a “quest” to “end” the simulation, to push the boundaries of the simulation for no reason other than collection’s sake. But to seek multiplicity in “endings” is to forgo the actual experience – purpose – of the narrative you currently inhabit. To prioritize choice-making in stories is to gamify narrative so that it is no longer about game content, what it shares or how it impacts the individual, but about game structure. Choices cannot be immersive if they are framed simply as another set of player quests and achievements.

What we should actually discuss is how can we design games that are technically innovative and narratively flexible without sacrificing them on the regressive altar of “choice.” Or, perhaps at an even more basic level, can we conceptualize the delivery of nonlinear, adaptable “narratives” in general without relying on “choice”? How can IF, how can engines like Twine, be used to this end? Twine’s resurgence was due in large part to its capacity to share accessible, diverse narratives through a digital platform. Twine does not need to be legitimized with the category of “video game,” nor should it be treated through such a prescriptive lens; rather, like the IF of the past, Twine products are effective at critiquing, influencing, and evolving digital storytelling.

Images: I captured all images as I played through the respective games.