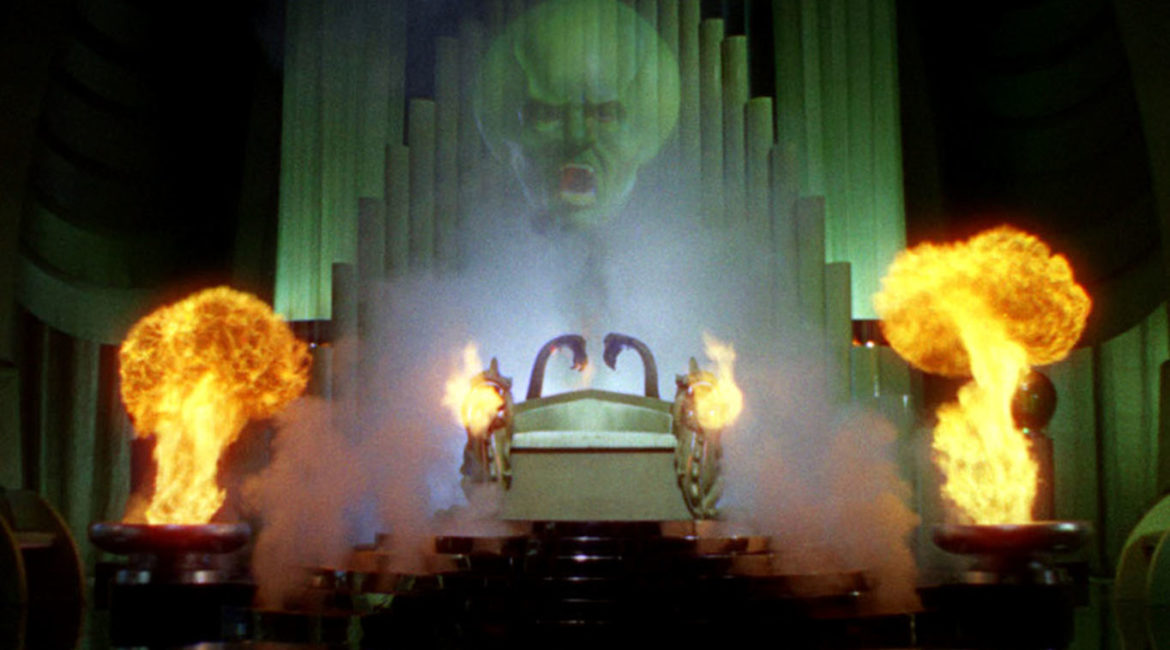

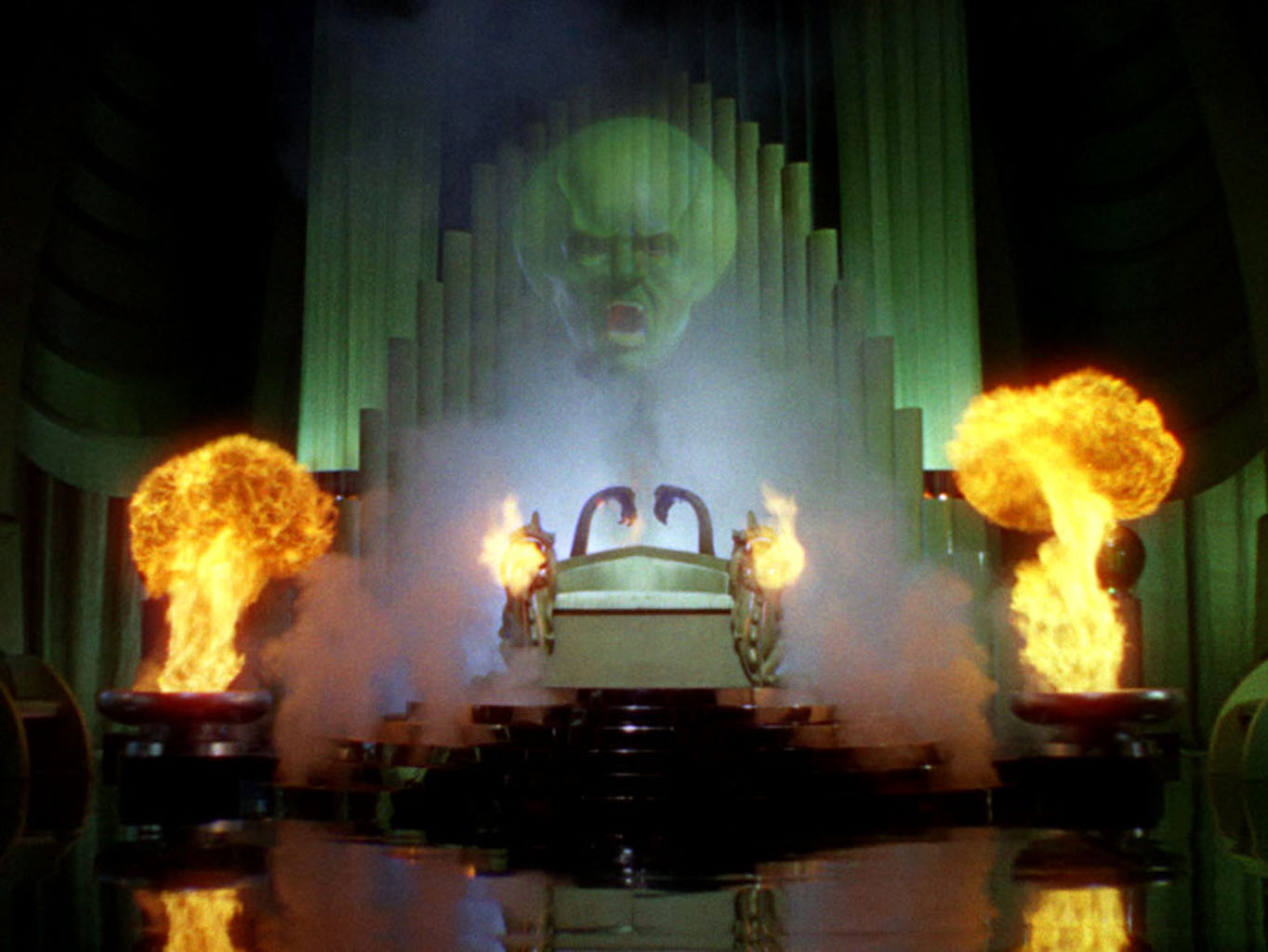

A couple years ago, I enrolled in my first digital rhetorics course. I was excited, but also insecure, certain that I was out of my league compared to my classmates, all of whom I assumed were naturals when it came to all things digital. Even though I knew this way of thinking didn’t make sense, I constructed a digital literacy binary of sorts: either you’re naturally techy, or not. A wizard born with magical powers, or not.

In a sense, this way of thinking echoes the myth of the “digital native” and the fraught pedagogy that can accompany this belief. I may not have been a teacher who assumes their students are all automatically fluent in some monolithic digital language, but I projected as much onto the rest of the class. (In her book It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens, danah boyd touches on the problems with the idea as well as the rhetoric of the “digital native.”)

Luckily, or perhaps predictably, the class disrupted this way of thinking. It was a space where we worked through our understanding of and experiences with different media and modes as well as analyzed their rhetorical affordances and limitations. Importantly, the class helped refute the notion that a person’s ability to use and compose with a particular technology is inherent or that it’s acquired passively.

This likely isn’t all that earth-shattering to those involved with the DWRL. Of course developing as rhetorically savvy digital writers is an ongoing learning process; otherwise, what are we doing here?

But it can be tough to know where students are on this topic, not only in terms of the anxieties or passions they may have toward composition, but also in terms of their physical, economic, and/or educational (in)accessibility to various technologies.

That’s definitely a loaded statement, but one possible way to incorporate and build from students’ experiences is through literacy narratives.

A resource for interested teachers is the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives (DALN), a public archive that encourages individuals to compose and submit stories (in text, video, image, and/or audio formats) about how they practice, learned, or teach a particular literacy. In a talk given at the DWRL in 2009, Cynthia Selfe, who co-founded the DALN, discussed the pedagogical benefits of literacy narratives, noting that exposure to these stories helped her better understand the literacy values her students brought to the classroom.

As someone who composed a literacy narratives in the aforementioned class, I had to learn to use a technology I was unfamiliar with (I used Twine, which is no stranger to the DWRL) to write about my experience learning another technology (I chose video games). What is perhaps more relevant to this post, though, is that I was exposed to a host of stories people had written where they detailed their experiences working with and learning various technologies. This helped me to pull back the curtain I had constructed of the all-knowing, great and powerful digital wizard.

Learning to navigate, compose in, and analyze digital spaces wasn’t impossible; it was just challenging at times, but I could learn, because everyone else who’s doing it had to learn. And that’s not nothing.