In an earlier post I discussed some of the difficulties we face in understanding augmented reality as a result of its many conflicting definitions. Fortunately, these definitions generally agree on a few elements: technology, mediation, interactive experiences, combining the non-digital and the digital. Unfortunately, just when we might feel like we’re able to comfortably describe augmented reality to anyone who asks, we’re confronted with another issue.

How is augmented reality any different than virtual reality?

Instead of attempting to provide any sort of sufficient answer to that question—partly because it would require far more time than this post permits—I’d like to suggest we follow the lead of the NYC Media Lab. In its December 2015 report called “Exploring Future Reality,” Executive Director Justin Hendrix explains that the title of the report is a reflection of the lab’s agreement with “NYU computer scientist Ken Perlin [who] wrote that he found himself struggling with the terms ‘Augmented Reality’ and ‘Virtual Reality’. Like many he imagines a future in which the distinction is no longer necessary. The phrase he suggests instead is ‘future reality,’ to describe a research agenda agnostic to any one set of technologies” (4). (Interestingly, the report then favors one term heavily over another: “virtual reality” appears 242 times; “augmented reality” appears 38 times.)

What I like about this approach is how inclusive and flexible it is. Rhetoric and the digital humanities, which is where my own work is situated, are two terms and disciplines that are constantly up for debate, whether that debate occurs internally (e.g., people within the field who are working to define it amongst themselves) or externally (e.g., explaining one’s work and one’s field to people outside of it). For instance, at UT Austin, there is currently the Department of Rhetoric and Writing, but rhetoric graduate students such as myself are technically part of the Department of English; moreover, there are also rhetoric students in our Department of Communication Studies .These two rhetoric-based groups frequently work alongside one another, but they are also clearly distinct from one another.

As these divisions suggest, rhetoric occupies some disciplinary gray area at the moment, moreso perhaps than disciplines like physics or history. The digital humanities is in a similar position, as the Debates in the Digital Humanities collection indicates.

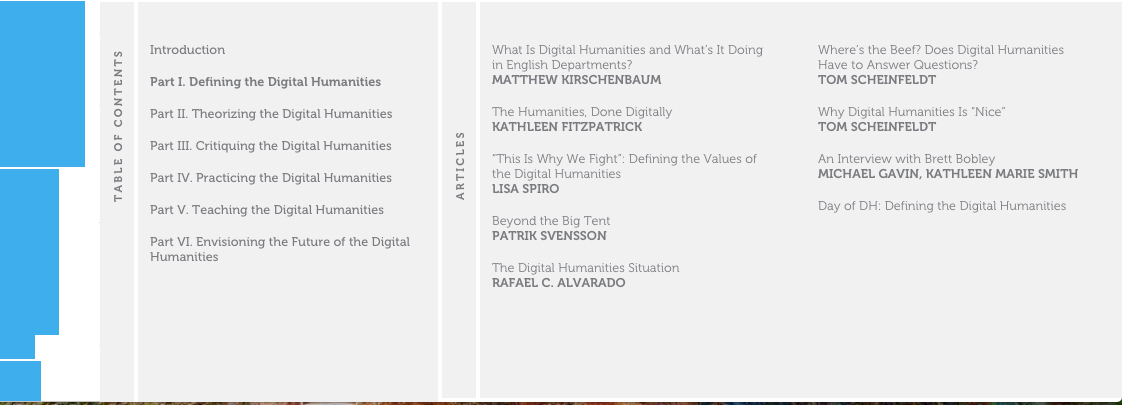

Notice some of the titles here:

- “What Is Digital Humanities and What’s It Doing in English Departments?” by Matthew Kirschenbaum

- “ ‘This Is Why We Fight’: Defining the Values of the Digital Humanities” by Lisa Spiro

- “Where’s the Beef? Does Digital Humanities Have to Answer Questions?” by Tom Scheinfeldt

This is what I love about the fields in which I work. At the heart of what I do is communication and persuasion, and these inquiries into who we are and what we do, into what our field is and what it does, undoubtedly leads to productive outcomes. The same type of conversation is clearly taking place around augmented reality. Regardless of what we call augmented reality, says the NYC Media Lab, “[w]hat is clear is that the time to experiment and invest is now” (“Exploring Future Reality” 35), which means actively thinking about not just what augmented reality does and can do, but also who it is for and why they would want it at all. That’s some good thinking, if you ask me.