We are, as others have pointed out, in the age of augmented reality. Whereas the twentieth century saw virtual reality develop in leaps and bounds, it is augmented reality that reigns supreme in the 2000s.

Case in point: the View-Master.

This toy, invented in 1939, is an early and well-known example of virtual reality. By simply looking through a small, binocular-esque device, users can completely block everything out of their field of vision except the photographic images contained on the “View-Master ‘reels’, which are thin cardboard disks containing seven stereoscopic 3-D pairs of small color photographs on film” (“View-Master“). As far as inexpensive toys go, this is a pretty neat one as is. In an effort to keep up with the times, though, the View-Master has been redesigned and is being marketed on its website as a virtual reality device that “will come alive with Augmented Reality technology.”

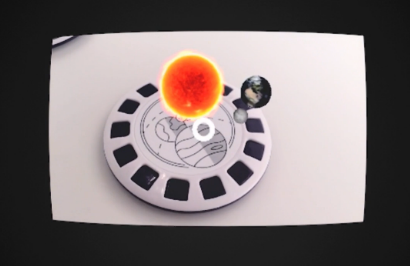

This updated View-Master now functions like a sleeker Google Cardboard: you (1) download an app onto your smartphone, (2) use your smartphone to scan a code that comes with the View-Master, and (3) slide your smartphone into the View-Master. Then, once you look through the View-Master, you can see digital images overlaid onto the non-digital world; in this case, an image that represents what you will find on a specific reel appears to float above the reel. When you select a reel, as the actors in its promo video explain, “you’ll be taken into a 360 degree world that completely surrounds you. Look up, down, all around. Everywhere you turn there’s something to see because you are virtually standing in that world.”

Wait a minute? Isn’t that still describing virtual reality? Frankly, yes, as far as the general definitions of virtual reality and augmented reality go. Besides the pop-up image that appears above the reels, this experience is a digitized version of what the View-Master has always offered: a visually immersive experience that replaces rather than builds upon one’s natural view of the world. Look, for instance, at what a user will see once they select a reel:

“You can pull up videos, images, fun facts, or mini-games,” but, no matter what you pull up, your interactive visual field is completely digital. This is hardly augmented reality.

Is that a problem, though? Perhaps not. As the actors point out in the end of the video, the significance of this device is that it “is an awesome way to learn. It’s a portal for kids to explore the world and beyond.”

This is no small takeaway for the field of rhetoric and composition, which continues to debate the complicated relationship between pedagogy and technology. As Jonathan Alexander and Jacqueline Rhodes note in their book On Multimodality: New Media in Composition Studies (2014), “students increasingly need to be versed in a variety of textual, visual, and multimodal formats if they are to participate as literate citizens and workers in an increasingly multimediated world” (12), but there are complicated factors for rhetoric and composition instructors to consider before and while they attempt this task. Nevertheless, we mustn’t shy away from this task because, amongst other reasons, we will not know what we can achieve with these unfamiliar approaches to what we do if we don’t experiment with them.

On the surface, we might write off this updated View-Master as no more than an fun, virtual-reality-based way for children to learn. What if there is more to it than that? Or if there isn’t, what could we do to make this kind of approach more productive for the adults we teach in our college-level courses? We won’t know the answers unless we keep playing.